The Architecture of Capture

How Erdoğan built an authoritarian state so sophisticated it doesn't need to hide. Judges still wear robes, parliament still votes, elections still happen, and none of it matters.

Türkiye's transformation under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan did not happen in a burst of chaos, but through a meticulous process of demolition and reconstruction, a gradual replacement of the republic's democratic core with a hollow but meticulously maintained shell. The genius of the system is not in its brutality, but in its subtlety: instead of tearing down institutions, it has gutted them from the inside and left the façades intact. This is why the country can still stage elections, seat a parliament, and maintain a network of civic associations, while in practice, all meaningful decision-making is routed through the presidential palace.

The first step was normalizing permanent exceptionalism. Following the 2016 coup attempt, the state of emergency, initially justified as a temporary measure, became the pretext for rewriting the rules of governance. Decrees issued under this extraordinary framework closed thousands of associations, purged tens of thousands from the civil service, and restructured the judiciary. When the state of emergency formally ended in 2018, many of these extraordinary powers were simply written into ordinary law. It was a constitutional sleight of hand: what had been emergency became baseline.

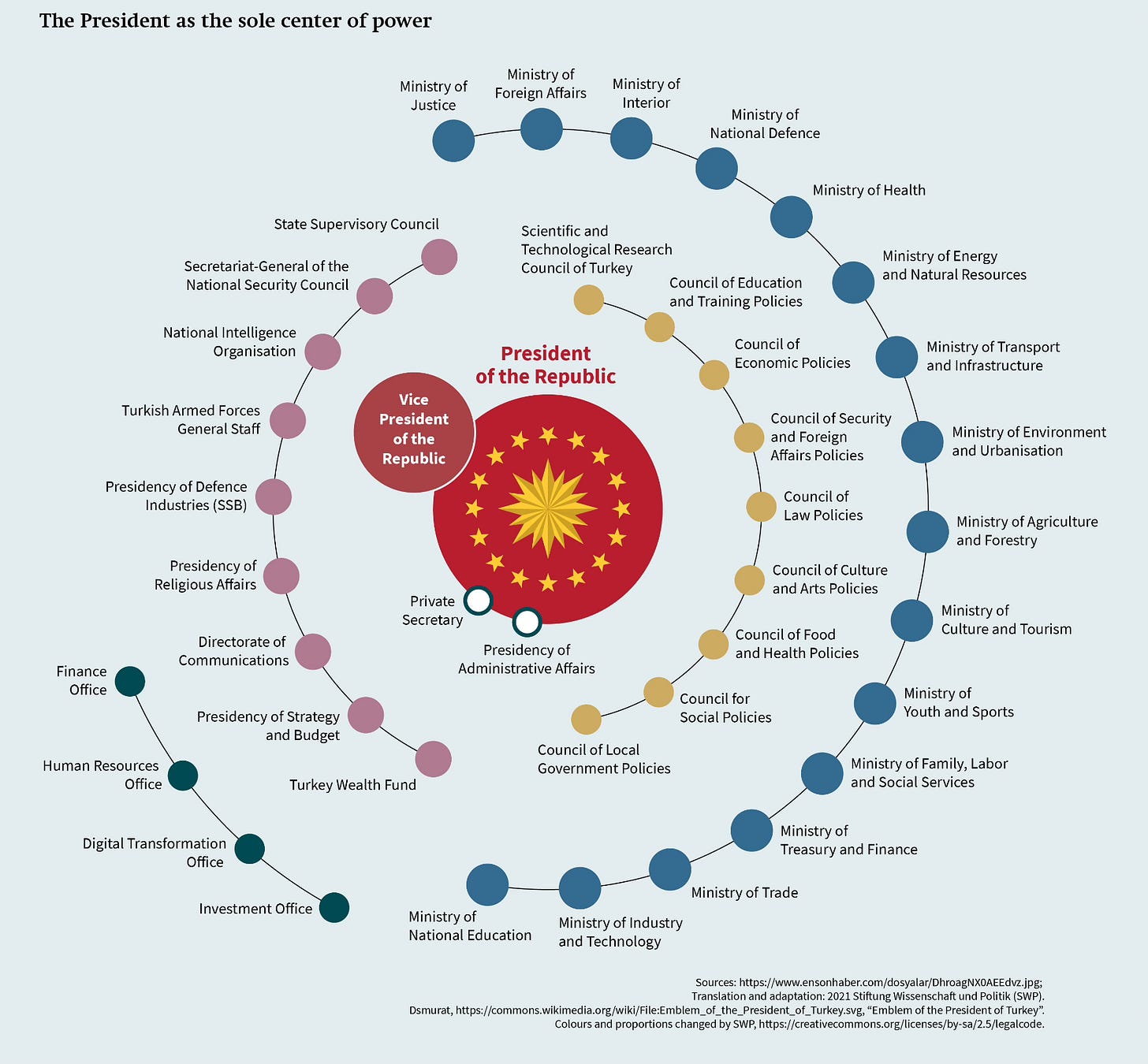

From there, constitutional engineering completed the transformation. The 2017 referendum, held under conditions of media dominance, intimidation, and electoral irregularities, abolished the prime minister's office and created an executive presidency with near-total authority. The presidency absorbed powers over the budget, judiciary, bureaucracy, and even the composition of key oversight bodies. Under the new model, the separation of powers was not eroded; it was obliterated. Parliament's ability to act as a check on the executive shrank to a constitutional mirage: MPs cannot directly question the president, and impeachment requires a two-thirds supermajority in a chamber the ruling bloc controls.

Elections became rituals of managed competition. Opposition parties can campaign and appear on ballots, but the terrain is mined. Electoral laws have been rewritten to advantage the ruling coalition, redrawing districts and altering seat allocation formulas. The Supreme Election Council (YSK), once a credible arbiter, is now packed with loyalists whose interpretations of the law invariably favour the presidency. Media coverage during campaigns is overwhelmingly skewed, not just through bias, but through structural access: opposition candidates struggle to buy airtime, while the president's rallies and speeches are broadcast live, uninterrupted, and in full.

The formal architecture of judicial independence has been dismantled in such a way that the courts now function as both shield and sword for the regime. The Council of Judges and Prosecutors (HSK) is the keystone in this system. Once designed to be at arm's length from the executive, it now consists entirely of members selected by the president or his parliamentary majority. Four are appointed directly by the presidency, seven by parliament (where the AKP-MHP bloc holds decisive control) and the remaining two are ex-officio presidential appointees. No judge in Türkiye is appointed or promoted without passing through this political filter.

This setup ensures that judges rise not on the basis of legal acumen, but on political reliability. The incentive is clear: rule in a way that aligns with executive priorities, and your career advances; deviate, and you risk reassignment to a remote province, stalled promotion, or disciplinary proceedings. This alignment has transformed politically sensitive cases into choreographed performances where the verdict is known before the trial begins.

The Osman Kavala case is emblematic, and rightly so. Despite an ECHR ruling demanding his release, Kavala remains imprisoned on charges widely seen as fabricated to criminalize his civil society work. In Selahattin Demirtaş's case, the courts have ignored repeated ECHR orders, prolonging his detention through a carousel of new indictments. In Ekrem İmamoğlu's case, the judiciary was deployed to sideline a high-profile opposition figure ahead of presidential elections through a conviction over a trivial stuff, a clear warning that even electoral success will not protect opposition leaders from legal neutralization.

At the Constitutional Court level, appointments have cemented control. Many current justices built their careers as prosecutors or lower-court judges in politically charged cases. Their loyalty is not merely ideological but structural: their advancement is the product of the system's political gatekeeping, and they know it. Even the highest court, in theory the last refuge for constitutional protection, now functions as a legitimizing body for presidential initiatives.

While judicial capture removes legal obstacles, media control ensures the narrative environment is favourable. This has been achieved not through wholesale closures or blanket bans, which would draw immediate international condemnation, but through market capture and regulatory strangulation.

Over 90 percent of Türkiye's media outlets are now controlled either by the state directly or by conglomerates whose wealth depends on government contracts, public tenders, or regulatory favour. These conglomerates are not neutral investors; they are political allies whose media properties function as extensions of the regime's communications strategy.

The process accelerated after the 2016 coup attempt, when a series of forced sales transferred major outlets into friendly hands. Newspapers that once published critical investigations now reliably produce pro-government headlines. Television channels, which remain the dominant source of news for most citizens, feature overwhelmingly favourable coverage of the presidency, with opposition figures given airtime mostly to be interrupted, mocked, or framed as dangerous.

Regulation plays the role of scalpel. The Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK) fines critical outlets for "unbalanced coverage" or "insulting the state" while ignoring blatant propaganda on pro-government channels. These fines, often in the millions of lira, bleed independent broadcasters financially, forcing many to scale back operations or shut down entirely.

The 2020 internet law was the regime's masterstroke in the digital sphere. It mandated that foreign social media companies maintain offices in Türkiye, making them subject to local law and therefore vulnerable to direct pressure. The law compels platforms to respond to government takedown requests within 48 hours or face throttling. Since its enactment, at least 336,219 URLs have been blocked, cutting off access to news reports, investigative journalism, and even historical archives that challenge official narratives.

The symbiosis between courts and media creates a closed informational-legal loop. The media frames politically motivated prosecutions as legitimate law enforcement; the judiciary punishes those who deviate from the officially sanctioned narrative. When opposition figures are arrested, state-friendly outlets echo the government's framing of corruption, terrorism, or "insulting the president." When journalists report critically, they face defamation suits, terrorism charges, or both.

On paper, Türkiye still boasts a vibrant associational life: more than 120,000 registered associations, hundreds of trade unions, professional chambers, and civic platforms. To the casual observer, or the visiting EU delegation, this can look like a pluralistic democracy in action. In practice, it is a landscape curated for safety and spectacle, where the organizations that survive either pose no challenge to state policy or actively amplify it.

The 2020 Law on Preventing Financing of Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction gave authorities expansive powers to inspect, freeze assets, replace leadership, and ultimately dissolve associations under extremely broad and vague definitions of "terrorism" or "security threat." The law is ostensibly about preventing the spread of WMDs, but in practice, it has become a versatile instrument for intimidating NGOs into silence.

Today, rights-based organizations face constant audits, administrative harassment, and targeted prosecutions of their staff. At the same time, pro-government "civil society" groups, often with Islamist or ultranationalist leanings, enjoy generous state funding, privileged media access, and close ties to ministries. They serve as both cheerleaders for government policy and as grassroots enforcers of its ideological line.

Parallel to the narrowing of civic space has been the unprecedented expansion of the Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet), which has become one of the most powerful and lavishly funded arms of the state. The numbers alone tell the story. Since 2006, the number of mosques in Türkiye has risen from 78,608 to 89,327 as of late 2023, now exceeding the number of compulsory-education schools. The Diyanet runs over 10,000 private Qur'an courses, manages 16,200 preschool Qur'an classes, and operates summer religious programs that reach nearly 4 million children.

Its budget tells an even more dramatic story: TL 16.1 billion in 2022, TL 35.9 billion in 2023, TL 91.8 billion in 2024, and TL 130.2 billion in 2025, surpassing the budgets of multiple core ministries, including Foreign Affairs, Interior, and Culture.

The sermons delivered weekly in over 89,000 mosques form a nationwide ideological broadcast network. While officially religious in tone, these sermons often align with government talking points on issues from foreign policy to "family values," reinforcing a moral framework that links piety with loyalty to the state.

Türkiye still maintains the formal institutions of economic governance: the Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye (CBRT), the Treasury, regulatory agencies. In reality, each of these has been subordinated to the presidency's priorities. Central bank governors have been removed mid-term simply for resisting presidential demands to cut interest rates in the face of surging inflation.

The Turkish lira has been in freefall for years, losing over 80 percent of its value against the U.S. dollar since 2018 and breaching TL 40 per USD in March 2025. The "FX-protected deposit" scheme introduced in December 2021 exemplifies this political economics: the state guarantees savers against lira depreciation, essentially betting taxpayer money against its own currency. By 2024, these accounts held ₺3.7 trillion ($115 billion), creating a fiscal time bomb that forces the government to keep rates artificially high while subsidizing the wealthy who can afford large deposits. It's redistribution in reverse, dressed as stability policy.

Foreign direct investment has stagnated at historically low levels: $5.6 billion in equity-capital inflows in 2023, $4.7 billion net in 2024, a fraction of what Türkiye attracted a decade earlier. These figures are not just economic metrics, they are the by-products of a governance model that treats economic policy as an electioneering tool. Stimulus is turned on before votes, austerity is applied only when crisis forces it, and any institution capable of independent judgment is brought to heel.

Under the pre-2017 parliamentary system, Türkiye's foreign policy was crafted by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs through a process of bureaucratic consultation and long-term planning. Since the constitutional overhaul, this process has been reduced to an extension of the president's personal political and economic strategy.

Ukraine and Russia exemplify this duality. Türkiye condemned Russia's invasion in 2022, enforced the Montreux Convention, and brokered the Black Sea grain deal. Yet it refused to join EU sanctions, expanded bilateral trade with Moscow, and openly welcomed Russian oligarchs' yachts and capital. NATO relations have followed a similar pattern, delaying Sweden's accession for over a year to extract concessions, notably a long-sought U.S. F-16 sale.

At the August 2025 BRICS+ summit, Erdoğan pushed for observer status and floated the idea of eventual membership, framing it as "strategic diversification" even while affirming NATO as Türkiye's security anchor. This hedging allows him to present Türkiye as indispensable to both East and West, an approach that maximizes leverage while avoiding irreversible commitments. What makes this fusion of economic and foreign policy particularly potent is how seamlessly they feed each other. Diplomatic alignments bring in cash infusions; those economic gains are then deployed domestically to stabilize support ahead of key political moments. Gulf deposits into the CBRT are not just financial lifelines; they are political endorsements with regional implications.

The system's true innovation isn't crushing dissent but pricing it. Every actor faces a carefully calibrated menu of costs: opposition leaders can speak freely but risk prosecution under 150+ different speech-related statutes; businesses can fund alternatives but face immediate regulatory retaliation; journalists can investigate but lose access, advertising, and eventually freedom. The genius is in the gradation, there's always just enough space to make total confrontation seem unnecessary, but never enough to build genuine alternatives.

This creates what economists call a "separating equilibrium": the bold are isolated and neutralized, the pragmatic are co-opted, and the vast middle learns to self-censor.

The West's approach to Türkiye has calcified into a three-part formula: (1) rhetorical concern about democracy, (2) practical engagement on security, (3) active avoidance of measures that might actually destabilize the regime. The EU's 2024 decision to unfreeze €3 billion in pre-accession funds, while simultaneously noting "serious backsliding" in its progress report, captures this perfectly. Money flows, refugees stay put, and everyone pretends the contradiction doesn't exist.

Perhaps the most overlooked dynamic is generational. Citizens under 30, who've known only AKP rule, have developed sophisticated workarounds that older opposition strategies ignore. They use VPNs as naturally as breathing (some reports show Türkiye has the world's second-highest adoption rate at 51%), conduct political discussions in gaming platforms and Discord servers invisible to state monitoring, and increasingly see emigration not as defeat but as rational career planning. According to the latest TÜİK dataset, Türkiye’s brain drain is accelerating. In 2023, 2.0% of all higher-education graduates left the country, the highest rate on record. Some fields are being gutted: nearly one in five molecular biology and genetics graduates departed, and ICT professionals are joining the exodus in ever-growing numbers.

This isn't resistance; it's circumvention.

The regime can live with it because it serves as yet another pressure valve: the most capable and potentially troublesome simply leave. But it represents a different kind of system failure: not dramatic collapse but gradual hollowing, where the state maintains its grip on an increasingly empty prize.

Türkiye under Erdoğan has achieved to create an authoritarian system so comprehensive that it no longer needs to hide itself. The façades remain, parliament, courts, elections, civic groups, but everyone knows they're façades. The opposition performs opposition; business performs independence; the West performs concern. It's method acting at civilizational scale.

What looks chaotic from the outside, policy lurches, currency whiplash, diplomatic zigzags, is coherent when read through regime survival. Courts criminalize adversaries and protect allies; media amplifies the criminalization; security services enforce it; the election referee sanctifies it; religious bureaucracy moralizes it; foreign partners normalize it. Even governance "inefficiency" is purposeful: by forcing decisions through the palace bottleneck, the system prevents autonomous power centers from forming.

The machine's perfection is also its vulnerability. Systems this centralized can't process complexity, only control it. They mistake submission for stability, exhaustion for acceptance. Every crisis requires manual intervention from the centre; every decision waits for the singular node. The president ages, the algorithms grow stale, the competent emigrate, and the world's attention drifts.

This isn't sustainable indefinitely. But "indefinitely" and "tomorrow" are different timescales, and the machine is built to survive every tomorrow that matters politically. The real tragedy isn't that Turkish democracy is dead, it's that its corpse is so well-preserved that everyone can pretend it's still breathing.